Reimagining Coffee

Inclusive Flavour Wheels in India

The SCA (Specialty Coffee Association) Coffee Taster's Flavour Wheel was first introduced in 1995. It is a widely recognized tool for describing and categorizing coffee aromas and flavours. It was developed to standardize coffee cupping and provide a common vocabulary for professionals and enthusiasts alike. The original wheel was updated in 2016 in collaboration with World Coffee Research (WCR), building on the Sensory Lexicon research. As much as I love this tool for guiding people to be confident in describing what they taste in coffee, over the past few years I have questioned how relevant it is globally. Following many discussions surrounding power dynamics in our industry, I have come to consider it as a eurocentric tool created by people in North America. All of the references in the Lexicon are required to be available for residents of the USA to purchase or access easily. However this does not make it a universal standard, as sensory and identification of flavours, smells and even tastes are all dependent on your personal life experience and context.

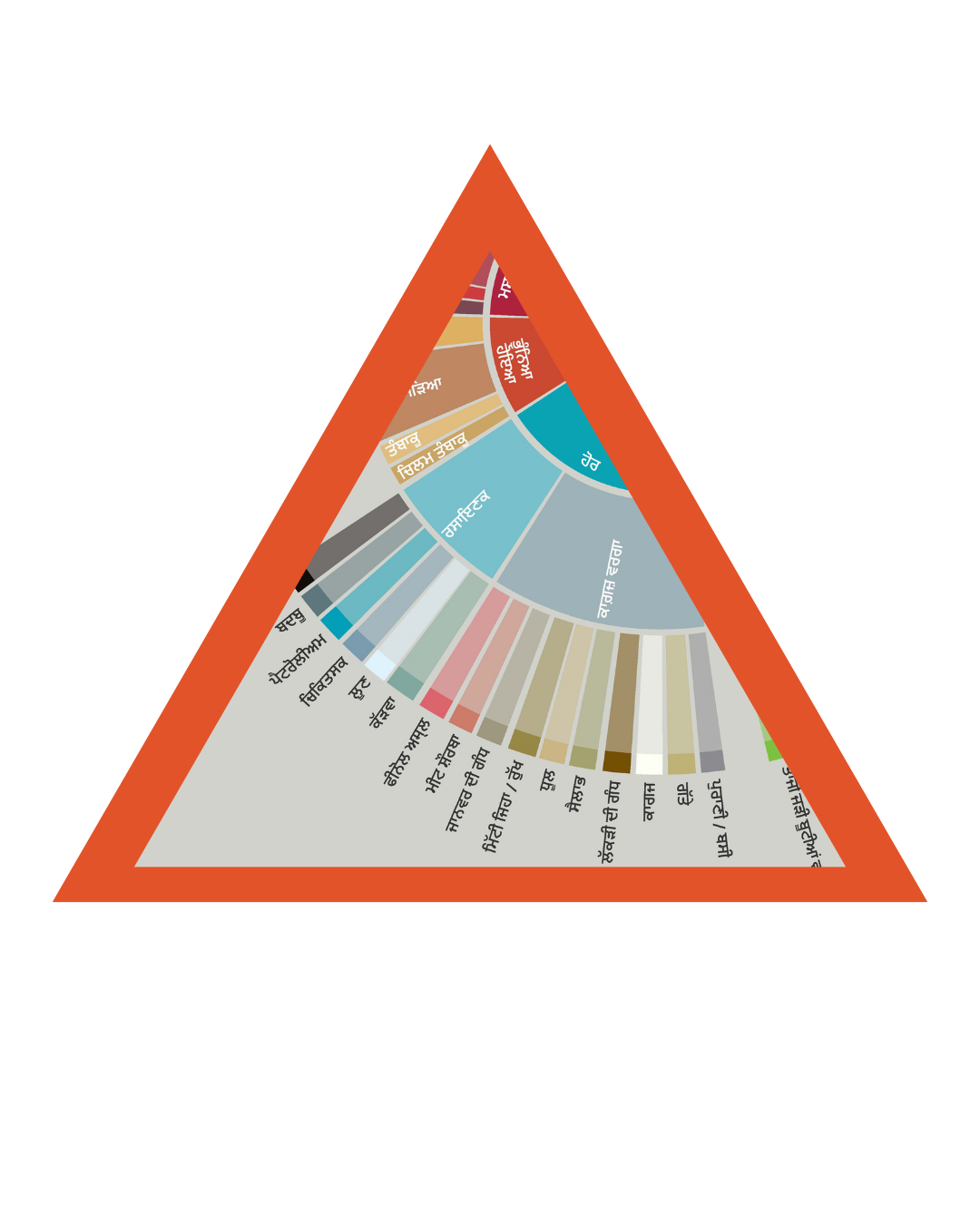

Binny Varghese, one of the founders of Barista Academy in India, has recently launched their own take on the flavour wheel in 7 different languages that are native to India. We actually first met during Covid on a video call for freelance coffee professionals to connect, organised by the wonderful Emma Haines, and since then I have followed his instagram @baristaonabike where I have enjoyed watching his adventures across India. You can imagine my excitement when I saw his posts about the Indian Native-Language Flavour Wheels, I had to reach out and book a call to learn more!

Binny Varghese and the Indian Native-Language Flavour Wheels

Binny began by explaining to me the frustration with the lack of education around the dark side of coffee and its history but said that it was bigger than just coffee. There has always been a global distinction between what is produced in the global north and the global south- and a great example of this is visible in the spirits industry.

‘You look at wine, you look at beer, gin, whisky- they are all considered to be such a premium beverage. But then when it comes to rum, tequila, coffee and chocolate, people don’t really talk about it in the same way- in coffee, the importance of origin only really got trendy in the last 10 years! And I feel something very similar is also present with the way people talk about flavours, and it’s very skewed to a particular population’.

Reconnecting with Local Cultural Contexts

Binny agrees that the SCA had very noble intentions behind creating the flavour wheel and that it was important to introduce some standardisation, but it was directed towards a group of people from a certain place in the globe. It was intended to be used by buyers and consumers in that area, and did not consider the producers and consumers of origin countries.

‘When you’re trying to use it, it does not really make sense, because it doesn’t fit the cultural and historical food and drinking habits we have’.

Binny gave an example of how pourovers, like a Panama Gesha, have extremely acidic/sour profiles. Many coffee professionals enjoy those brews because of that flavour, but it is not enjoyed by everyone.

‘If you look at the food habit and cultural influence of drinks, specifically in Asia and Southeast Asia and India, we culturally don’t have anything that is hot and sour- it is a very odd combination on our palette and our initial reaction is that we don’t like it, and it tastes like something that is probably not pleasant’.

He expresses a similar discrepancy with flavour references. There are many flavours in the wheel that when they are teaching, people cannot relate to it because it is not indigenous to them. Binny explains that blueberries, for example, are imported and expensive- so the local indigenous people are not supposed to know what that tastes like, or have a reference for it in their memory.

‘Most baristas and farmers, don’t have money to go through sessions, classes and certifications and they are the ones who end up working in the industry, so if they cannot relate, then it’s basically just them making up different flavour notes and just talking to people about it, which does not make sense’.

In this case, it takes the authenticity and experience out of tasting coffee, it becomes robotic, which limits progression in the industry. He compared it to a roaster having access to a Colour Metre and then explaining to their customers ‘This coffee is 76.3 Agtrons’. It is meaningless without any understanding of the context, but using language like ‘medium roast’ is going to give the customer more clarity of what to expect.

-

When it comes to identifying flavours, smell is hugely important. Essentially when you smell something, it sends an electrical signal to your brain. Your brain then races through all of your memories to try and identify where it has ‘experienced’ that specific signal before to give an interpretation of the smell.

-

If it is something you have smelt regularly, for example, chocolate, the neuropathways are extremely strong, and so very quickly your brain will recognise and interpret that electrical signal. You smile, and think ‘ooooh chocolate!’, it will likely trigger a positive memory (unless you have made yourself sick eating too much chocolate in one sitting!!).

-

If it is something you have smelt before, but not often, I like to picture the brain as someone in an old library surrounded by rows and rows of books. When the impulse comes in, your brain races through the books, grabbing them and opening them one by one in a panic and discarding them on the floor behind, saying with exasperation, ‘where is it?!’

If I was then to come in and say ‘that smells like honey to me’, your brain would hurry to the section with all of your memories of honey and say ‘does this match?’ as it flicks through the pages. And when your memories of honey match up to the smell, you let out a sigh of relief ‘well of course it’s honey! I can smell it now’.

With practice and repetition, those neuropathways get stronger.

-

However, if it was a smell that you had never experienced before, your brain would have no reference point for that smell as it would be a completely new experience for you. Your brain would not be able to ‘connect the dots’ so to speak- it would be a blank point. So if someone has never eaten a blueberry before, or something blueberry flavoured, then they certainly wouldn’t experience that in a cup of coffee, they have no reference or memory for it! This is why it’s so important to talk about coffee using language and food and drinks that are familiar and consumed regularly.

Accessible, People-Focused Flavour Wheel

The original Lexicon is very scientific and lab oriented, and Binny wanted to make theirs more people focussed and accessible. So although Binny did the Hindi language wheel first himself, he prioritised collaborating with local people who do not work in coffee to create the wheels in the other languages. Their names are featured in the final prints.

‘This means there is less subconscious pretentiousness in terms of flavours and it’s genuinely a good scope of what people are used to tasting’.

There are certain words, like petroleum, which do not have a translation or the translations don’t make sense because nobody uses it, so the local colloquial would be ‘petrol’. But there are nuances in things like describing sour fruits.

‘Instead of blueberry, we have a Hindi or Indian alternative we call Jamun, or for roasty flavour, we used a simplified version which is how we talk about roasting meat or nuts that you would say at home’

Binny says although they have translated this flavour wheel into 7 languages and counting, his favourite one that takes centre stage, framed in the academy, is the blank one.

‘I want people to have an indication that coffee can be anything they want it to be- not what someone else is thinking- it’s all about what you have in your memory bank, and you’re taking a piece out of it’.

By having an empty flavour wheel it is encouraging people to take agency over their own experience of coffee and relating it back to something they have smelt or experienced before- not just picking out what you think someone else would want you to taste or say.

There are between 40-50 native languages and then beyond that, dialects that are very different from each other, so this is a project that is only beginning. People are now using social media and whatsapp more where they type their local dialectical language using english letters, so english transcription wheels are also being created.

The Growing Reach and Impact of Indian Language Flavour Wheels

The wheels have rolled out across India, through people who Binny has worked with in consulting, or those educated at the academy. People working abroad are using it and it’s gaining traction through social media. Anyone can reach out to Binny for a copy in any of the languages. The only fee is to donate money to any charity or any cause, and send a screenshot of your donation to receive your copy. If you send your logo, he will co-brand it either with your logo, or a name that you prefer, personalised.

Binny explains the reaction has been hugely positive- people appreciate having any Western concept put into their own context- but explains the goal is a longer term strategic shift in mindset. In India, often a premium experience is correlated with the English language.

‘Communicating in English, people often automatically think you’re knowledgeable- it runs in a lot of industries and coffee happens to be one of them- and I wanted to break that’.

Binny competed 2 years ago in the Indian Barista Championship with a focal point on language. He didn’t use any flavour notes that were English or western inspired. His notes only related to local Indian food and beverages, yet his feedback from the judges was that he should make it more complex.

‘The bigger reaction that I'm looking at is the fact that they’re aware that this is available in other languages- that makes things immediately less intimidating. It makes it relatable to something they know in their own languages.’

By having a flavour wheel in your own language with your own references, immediately makes it relatable and comforting. It brings authenticity and encourages people to be more inquisitive when they are tasting coffee. The hope is that this idea grows and that people will realise that they can make a flavour wheel themselves, in their own language too.

‘My motive in the industry, is how simple can we make it, but the problem is with the education in our sector, its quite the opposite, we put in so much science and technicality’

The Future of Coffee Education: Simplifying and Connecting

We need to bring back simplicity and joy in coffee and that includes using a language that people can relate to and talk about together. A real experience and of understanding the sensory qualities of a cup of coffee shouldn’t only be for ‘experts’. Frustratingly, we have built a culture, even as professionals, that fusses around brewing ‘the perfect cup’ and we are worried about judgement and criticism. We can’t even make someone else a coffee without a pre-warning, ‘sorry, my grind size was a bit off’ before serving it to them. These are habits we pass onto people as they progress through the industry, and even consumers begin to pick up our bad habits, exclusively over complicated ‘standards’ and subtle imposter syndromes.

Binny finishes by simplifying it again down to this:

‘For me, the definition of a good coffee, is would you pay to have this same coffee and service again? If yes, then it’s a good cup of coffee’.

CONCLUSION

The emergence of Indian Language Flavour Wheels marks a powerful and necessary step toward a more inclusive and culturally grounded understanding of coffee. While the SCA flavour wheel has given a framework and standardization for the industry, its eurocentric roots can unintentionally alienate those whose sensory memories and references lie outside of that cultural frame. Binny and his team’s efforts highlight the importance of reclaiming coffee-tasting language and rooting it in local experiences, languages, and traditions; especially in producing countries that have historically been left out of the conversation.

This movement is not just about translation; it’s about transformation. It asks us to rethink who gets to define the coffee experience, whose palate is prioritized, and how language, memory, and culture shape our understanding of taste. By inviting baristas, farmers, and everyday drinkers to describe coffee in terms that are meaningful to them, the Indian Language Flavour Wheels are opening the door to greater accessibility, confidence, and joy in coffee tasting.

As the global specialty coffee industry continues to evolve, efforts like Binny’s remind us that true progress lies not in complexity, but in connection. By shifting away from prescriptive, intimidating standards and toward authentic, culturally relevant approaches, we can build a coffee culture that is more diverse, inclusive, and sustainable—one where everyone’s sensory memory has a place at the cupping table.